Big Ben

© 2007

Armchair Travel Co. Ltd. - This page may be used for non-commercial purposes

ONLY!

![]()

[ Play

Narrated and Animated Movie ! ] Big Ben, was designed and cast under the supervision of Edward Beckett Denison, a leading expert on clocks and bells. The first bell was brought by sea from the north of England, but on being tested, cracked. A second bell was commissioned from Mears in Whitechapel, and was raised with some difficulty to the Belfry. However this too cracked, but it was found that by turning the bell and reducing the weight of the clapper it sounded satisfactorily, and has continued to do so, with minor interruptions, every hour for the last one hundred and forty years.

After the tragicomedy of the production of the great clock at the Palace of Westminster, it might be supposed that all concerned had learnt their lesson and that the process of selecting a manufacturer, producing the bell, hoisting it into place and testing it would have proceeded smoothly. Such alas was not to be the case, indeed if the former episode could have been politely described as messy, the latter was a real rough house.

At least Barry had benefited from the earlier experience and, on being asked by the Office of Works for his views in 1854, recommended that George Mears should be preferred but that if a competition were required, Warner and Sons and two other well-known bellfounders be approached. He even recommended that Edmund Beckett Denison be consulted to draw up the specification and that the resulting bell should be superintended and certified by Beckett Denison and the Reverend W. Taylor FSA, noting that the former was "well acquainted with the manufacture and requisites of bells". The Office asked Beckett Denison to prepare a specification which he promptly did and submitted, with the advice that Warner's tender should be accepted if it was within reason because they had patented a new method of casting bells which 'arrived at the best form and thickness for large bells'.

The Office accepted Beckett Denison's specification but the First Commissioner of Works, called Molesworth, had added his name to the referees. On hearing which Beckett Denison wrote that he would be no party to such foolishness since the Commissioner knew nothing about bells and might be succeeded at any time by another who was also ignorant of the subject. Luckily, at this point Molesworth was promoted to a more senior position in the Government and Sir Benjamin Hall, a man generally recognised to be the outstanding holder of the office in the 19th century, took over. Hall immediately replaced all of his staff, who were in the habit of being absent most of the time, and got on with the job of getting a bell for the Palace of Westminster. Beckett Denison was back and the casting of the bell was duly completed at Stockton-on-Tees in August 1856.

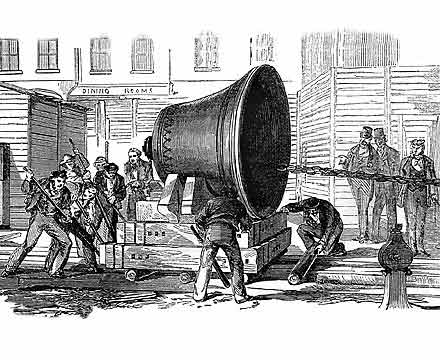

The casting was deemed to be a success, although it had come out much heavier than expected, some fifteen and a half tons, and was shipped down to London on a small boat capable of going under London Bridge. The bell nearly sank the boat on loading as it was dropped the last foot onto the deck, however it duly arrived in London and was drawn by sixteen white horses over Westminster Bridge amid wild scenes of enthusiasm from a huge crowd which the police had some difficulty in controlling.

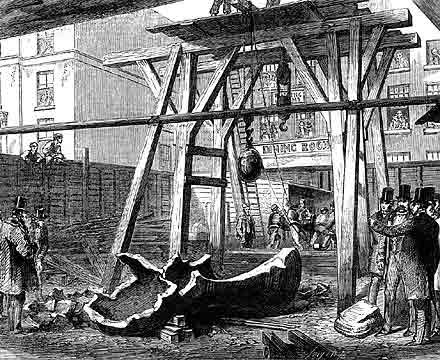

After some testing it was discovered that the frame, designed by Barry, was too weak to allow the bell to be raised up the clock tower. The bell remained at Westminster whilst Warners cast the accompanying quarter bells, and then, during further testing, the bell cracked. There were the usual recriminations with everyone blaming everyone else; Beckett Denison, who as usual had the last word, claimed that the bell was too heavy and the waist too thick. Whether he was right could not be proved, but there is some evidence that the bell was malformed because the metal ran short during casting. In any event another bell had to be called for. This time Mears won the contract and in 1858 the old bell was broken up and the metal sent to their foundry in Whitechapel.

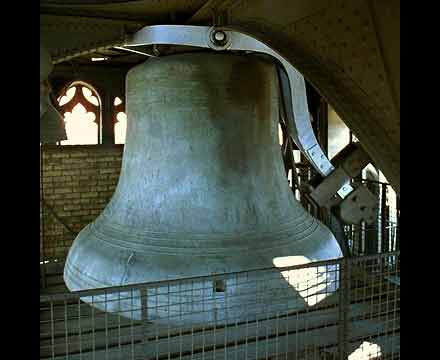

The bell they cast was more than two tons lighter at 13 tons 10 hundredweight, with a slimmer waist. Even so it was no easy task to raise the bell up the tower, since Barry had designed the tower without considering the bell. In fact the bell was of an unconventional shape to allow it to fit up the tower and even then had to be placed in the lifting frame on its side to travel up the narrow (11' by 8' 6") shaft. On arrival in its position, it was found that the collar and standards of the frame were not strong enough; Barry had failed again and had to set to work replacing them. It was then found that the bell had been bolted up too tight and that further adjustments needed to be made.

There was now considerable public anger in The Times and elsewhere about all the delays, which was fuelled by the release of the figures for the costs of the clock and bell. Of a total cost of over £22,000, a huge sum in those days, Barry had very ingeniously prepared the allocation and attempted to put much of the blame onto Beckett Denison, who naturally did not take this laying down. Punch magazine meanwhile wryly commented that it was a good example of the dictum that "Time's money".

However with all the bells, and the clock below them, now installed and the hour bell ringing out to be heard as far as Camden Hill and Richmond Park, it only remained to add the hands. It was now discovered that the minute hands, an artwork designed by Barry and Pugin, were too heavy to go round. Barry blamed Beckett Denison who replied (with some splendid invective) in a letter to The Times that he had specified a weight of eight hundredweight, but that they had been manufactured to a weight of twenty-five hundredweight. They were soon redesigned to the lighter weight, and new ones fitted. The four hour hands, made of gunmetal, are each 9ft long and weigh 6 hundredweight each. The minute hands, of copper sheet, are 14ft long and weigh 2 hundredweight each.

On the 29th September 1859 the Mears bell cracked. The Times and Mears blamed Beckett Denison for the bell being bolted up too tight. He replied that the architect had been responsible for the fitting and had ignored his instructions, that the bell had been badly cast and that it was porous, with numerous holes in it. These had evaded his inspection because "they had been filled up by Mears as a dentist fills teeth with some amalgam and then covered up with a coloured wash". In short it was a fraud. Mears sued Beckett Denison for libel and because the Office of Works refused to let either party take a lump out of the bell for analysis, Beckett Denison had no case and was forced to apologise. A month after the case the Office had a piece cut from the bell - the hole is visible to this day - and examined by an expert who pronounced that the metal was unhomogeneous and therefore the bell casting was indeed bad. Nevertheless, after being turned slightly to avoid the hammer hitting the crack, (and indeed with a lighter hammer) Big Ben has rung out continuously on the hour for almost one hundred and forty years.

Beckett Denison's abrasive and assertive nature had won him few friends though he was not a man to be deflected from his chosen course by mere popularity seeking. In spite of losing the libel case, being vilified in the Press, and heavily criticised by the Government and by the architect of the Palace, it eventually came to be generally recognised that without his efforts, given freely, without any charge to the public purse, over a period of ten years, the Palace would have had neither a clock nor a bell worthy of the name. It is ironic that one of the least loved (other than by his family) of the great Victorians should have been primarily responsible, against tremendous odds, for the heart of one of the best-known and best-loved landmarks in the world.

As to the origin of the name 'Big Ben', it would be tempting to confirm that it alluded to the generously proportioned Sir Benjamin Hall, one of the few heroes of the story, who despite (or more probably because of) his exceptional administrative talents (and envy thereof) never held another Government post. However it is almost certain that the name was given to the bell by the workers at Warner's bellfoundry during its casting and which referred to the unbeaten prize fighter of the same nickname born in 1753 near Bristol, who died three years after defeating the champion of all-England, Tom Johnson, in a famous match in 1791. A third source could also have been Ben Caunt who was the bare-knuckle champion of the early 1850's and was also known as Big Ben.

[ Virtual

Tour ] [ Main Topics

Index ]

Additional Information on

Big Ben

Explore-Parliament.net: Advanced Category Search

Keyword Categories:

_Consort

_Setting_Westminster

_Setting_England

_Object

_Ben